Nature As Inspiration in Garden Design

Designing with nature requires the designer to develop heightened awareness, not just of suitable plants for a specific location, but of climate, prevailing wind direction, exposure, aspect, gradient, soil type, indigenous vegetation, geology, threats from animals domestic and wild and the site’s general ambience and atmosphere.

Every garden is unique and your job is to recognise, explore and exploit this genius loci – sense of place. Such wide-ranging knowledge will equip you with the confidence to make selective decisions about the garden you are employed to transform, or optimise. Nature can be a great help. Use it. Make notes on-site about every detail, positive or negative, problematical or inspirational. You will learn to look for these vital signs and keep a checklist handy. These are the building blocks that will inform every decision you make during the design process.

A fundamental precept of designing with nature is to work with it, not against it. Not everyone recognises that it’s a bad idea to site a pond on top of a hill – ponds naturally occur in sunken areas, usually drained from higher land – or to attempt a tropical garden in a frost pocket.

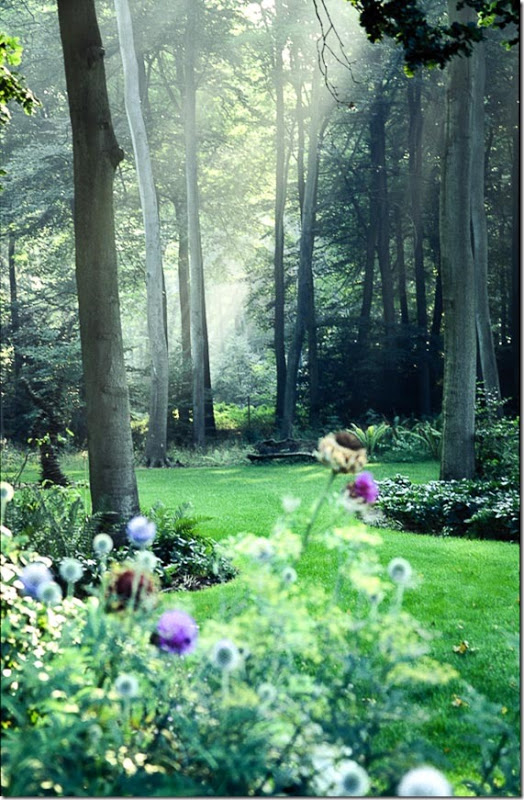

If you are commissioned to design a garden in a rural setting, aim to fit the garden comfortably within the surrounding landscape. Echo in your ground plan or in the shapes of plant groupings the patterns, rhythms and colours of rolling farmland , outlines of hills or mountains, or the vertical shapes of tree trunks in a woodland setting.

Harness the light-giving properties of water to reflect changing cloud patterns via ponds, brimming half barrels or even just a few judiciously sited wide, shallow stone or metal bowls. If there are windblown dunes of marram grass nearby, borrow this look, planting cultivated grasses that move with the breeze – another natural element. If the site is boggy and badly drained you don’t need to persuade your clients to spend thousands of pounds drying it out.

Forget rose gardens, and herbaceous borders and go with the flow, quite literally. Ensure the soil is not sour or compacted and create a wetland garden. Your expertise in gaining your client’s confidence is essential, as they may have fixed ideas as to what they want, but scant appreciation of the hassle and cost of achieving sometimes unrealistic or over-ambitious aims.

Houses on new or established suburban estates may not reveal any immediate natural characteristics, so can be treated more or less in isolation. However the same guidelines apply to the specific properties of the site. A small patch of soil or lawn (often containing hidden builders’ rubble – beware!) can hide several different challenges – from wet to dry, acid to alkaline, shaded to sunny, sheltered to exposed.

All of these occur more or less naturally and must be observed and respected or corrected. But don’t make more work for yourself and more expense for your client if it isn’t necessary. You can still achieve a design that delights both of you.